Two novels I’ve read in the past year stand head and shoulders above the rest.

The first is Chaim Potok’s The Chosen, published in 1967. The only surprise here, if you know my literary tastes, is that it took me nearly half a century to pick up and read this classic exploration of religious life. There are certain gaps in my literary experience, I readily admit — but this is no longer one of them.

(Another conspicuous gap is J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951). I know it is had for both good and evil, and was banned within my lifetime in a certain Washington school district for being part of a communist plot. All the same, a young writer I met at lunch a few weeks ago talked me into reading it sooner rather than later. I’m too old, among other things, to be drawn to it for its rebellion and teenage angst, but it has other charms. After reading just the first two pages, I’m inclined to appreciate — and to study — the first-person narrative voice. But I digress.)

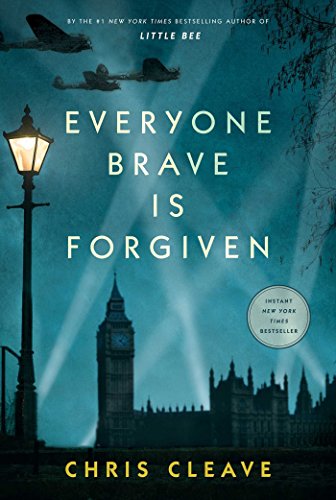

The second highlight of this year’s novel-reading is Chris Cleave’s Everyone Brave Is Forgiven, first released not five months ago. Cleave’s first three novels, which I haven’t read, were well received and have contemporary settings. This fourth offering is historical fiction, set in England and Malta during the early years of World War II — mostly before the United States joined the conflagration in December 1941.

This book is delightful but substantial reading. Though often light-hearted, at times it is grimly realistic and personal about the physical, emotional, and moral horrors of war. It has some thoughts on race and class, but (thankfully) isn’t heavy-handed about them. This virtue displeased the subset of reviewers who declare even a brilliant novel disappointing, if it does not bludgeon the reader with proper and comprehensive modern views of any social issues it happens to touch.